It’s hard to imagine today, when newspapers, magazines and blogs are full of articles about the malfeasance of government, that there was a time when nobody spoke about the dark side of the CIA or the secret spy networks of the FBI.

It’s hard to imagine today, when newspapers, magazines and blogs are full of articles about the malfeasance of government, that there was a time when nobody spoke about the dark side of the CIA or the secret spy networks of the FBI.All that changed in the 1960s with Ramparts Magazine.

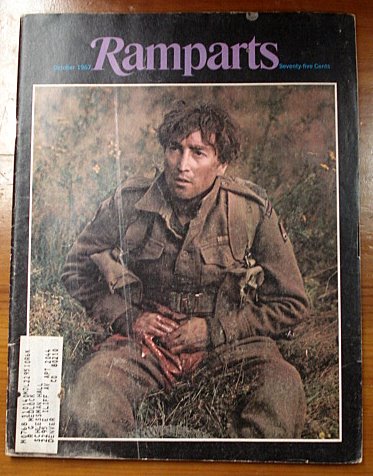

For those who don’t remember, Ramparts was a slickly produced magazine of the left and a publication that took no prisoners. Started in Menlo Park as a Catholic literary quarterly in 1962, Ramparts evolved into one of the most important periodicals of the New Left. The magazine exposed the close relationship of universities with the American war machine, revealed the ugly truth behind the Vietnam War, and trumpeted the power of a new protest group called the Black Panthers.

And it all happened in the Bay Area.

Now Peter Richardson, an editor at PoliPoint Press in Marin and a lecturer on California Studies at San Francisco State has written the definitive history of the brightly-shining but short-lived magazine. A Bomb in Every Issue is a long overdue look at this important periodical, and it’s mighty entertaining as well.

It turns out that the Bay Area was critical to Ramparts’ success because the region served as a cross roads for sophisticated marketing, radical culture, smart, aspiring writers, and a willingness to break traditional social conventions. Take the Free Speech and anti-Vietnam movements in Berkeley, the Black Panthers in Oakland and the Summer of Love in San Francisco and you have an explosive mix of rage and energy.

Into this heady brew came a group of outsized characters, many of whom have become important historical figures in their own right. Ramparts was started by Edward Keating, a Stanford-educated lawyer and Catholic convert who recruited Thomas Merton and John Howard Griffin, the author of the seminal Black Like Me, to write for him.

Keating eventually hired Warren Hinckle to do publicity for the magazine, and Hinckle soon stepped up as editor and moved the periodical to San Francisco. With his eye patch, large girth, hard-drinking ways, as well as flair for attracting attention to his projects, Hinckle transformed the magazine. Ramparts became a well-produced, eye-catching glossy that said “Read Me” all over it instead of “This-is-just-another-boring-radical-rant-on-newsprint.”

Hinckle’s smartest move was to hire Robert Scheer as a writer. Scheer was then a struggling graduate student at Berkeley and Richardson writes some amusing anecdotes of the scrapes he got into. (Including the time he rode in his motorcycle across the Bay Bridge but forgot to secure his master’s thesis. It was his only copy and soon it was scattered all over the freeway. Scheer never did get that degree.) Scheer wrote many of the explosive stories detailing the cloak and dagger work of the CIA.

I was really surprised to discover that Eldridge Cleaver rose to prominence because of his work at Ramparts. Keating printed some of his prison writings and even helped Cleaver get out of jail. After working for Ramparts for a time, Cleaver joined the Black Panthers and became internationally known.

Richardson’s book is full of other tidbits. Hunter Thompson wrote for the magazine, as did Howard Zinn, Norm Chomsky, Susan Sontag, and Tom Hayden. Ralph Steadman provided illustrations. Jann Wenner worked at the magazine and then left to form Rolling Stone. Adam Hochschild worked there, too, and later founded Mother Jones. David Horowitz, today considered a major neo-con, started out as a radical writer at Ramparts.

“What really distinguished Ramparts from other publications was its ability to compel bigger news organizations, especially the New York Times, to pick up its stories,” Richardson told Andy Ross on his Ask the Agent blog. “All told, the Times covered about a half dozen Ramparts stories on its front page: for example, when Ramparts revealed that the CIA was secretly funding the National Student Association. And during the late sixties and early seventies, Time magazine ran about ten stories about Ramparts, mostly to disparage it. But all those stories did was raise Ramparts’ profile.”

All those strong personalities had strong egos, which invariably clashed. First Keating, then Hinckle, and then Scheer got ousted. The money started to trickle away. Ramparts reverted to newsprint, but even then attracted strong writers such as Angela Davis, Seymour Hersh, Alexander Cockburn, Jonathan Kozol and Kurt Vonnegut. Finally, after other muckracking institutions, including CBS’ 60 Minutes came on the scene, Ramparts started a steep decline and folded in 1975.

This is not a love letter to the left. Richardson raises some very serious questions in the book about the activities of the Black Panthers and local politicians. In 1974, Elaine Brown, the leader of the Panthers hired Betty Van Patter, an accountant, to help with the organization’s books. Van Patter apparently started to ask some hard questions about the Panthers’ money. She disappeared in December 1974 and her body was found on a beach a few weeks later.

Richardson discusses how misinformation about Van Patter was spread and how many officials preferred to look the other way. In particular, he singles out the reaction of Congresswoman Barbara Lee, who wrote in her own book that Van Patter had a prison record (not true) and disappeared with a large sum of money six weeks before police found her body. Lee suggests that the accusations of her death by the Black Panthers are just anti-left propaganda. It’s a sobering reminder of the toll that period did take.

Richardson has planned a series of readings and talks that should be a wonderful and thoughtful romp through the radical 1960s. He will be speaking with Robert Scheer on Thursday September 24 at 7:30 pm and Berkeley Arts & Letters; at Book Passage with Norman Solomon and Reese Ehrlich at 7 pm on Friday Sept. 25, and at the Huntington-USC Institute for the study of California and the West on Oct.6. His complete schedule is here.

2 comments:

I love your blog. You go places we need to go. Please do more. Thanks Thanks Thanks.

- jim

Not a word about David Horowitz as one of its main writer and editors, why?

Post a Comment